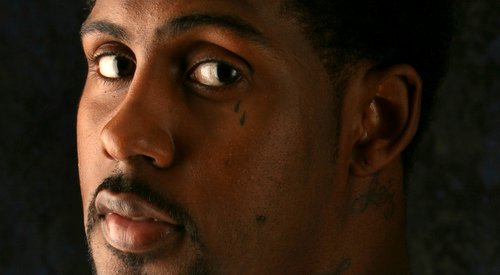

The Times and Life of Larry Hughes: A Biography in Reverse

Larry Hughes has been a lot of things to a lot of people, but since I’m neither you, him nor a tortured sports fan in Cleveland, I have to focus on the life of the man from my own perspective. From where I’m sitting, Larry Hughes is a traditional Russian stacking doll of NBA stereotypes, a beacon of mortality among a landscape of gods, and a story best told backwards.

And so the end begins.

Chapter 6

It’s the late aughts, early twenty-teens and Larry Hughes is an afterthought. Worse, a punch line, a decrepit relic of an awkward, temporary phase of the NBA’s post-Michael Jordan transition. The man is culturally non-existent.

At 6’5” and a lithe 185 pounds, the 30-plus-year-old sails around the court like a ghost, purposeless. He’s a Bull, he’s a Knick, he’s a Bobcat. He’s an unsigned free agent. Least of all, he’s a contributing veteran member of a young basketball franchise in desperate need of leadership like he ought to be.

Not even Magic could save him.

Like the droves of millennial swingmen he broke onto the professional basketball scene with back in the late 1990s, Hughes stands today a broken down, relic of the once-next generation. He’s not alone. The list of high-athleticism, higher-potential wing players tagged as the new inheritors of the NBA at a time when it sorely needed some is a lengthy one.

Like aging child actors we watched Swingman Incorporated fall. Isaiah Rider, Jerry Stackhouse, Tracy McGrady, Vince Carter, all once cast as the future of the position ultimately came up short of the lofty goals they sought to achieve. Worse than failing to live up to their own expectations, however, they failed to live up to ours.

[php snippet=1]

Time hasn’t been kind to the once-revered, super-wing. Apparently it’s harder than it looks to carry an NBA franchise on one’s back with little but a 40-inch vertical and an ounce of marketability.

Neutered by the cruel punishment of passing time, the veterans wander throughout the modern day professional basketball world, dated, out of fashion and unable to play the game effectively without the slashing and jumping ability that made them famous. Maybe J.R. had the right idea opting for prison, after all.

Chapter 5

About 10 years ago things truly started to take form for Hughes, and from 2004 until about 2006, it seemed as though the world had finally learned to appreciate what he offered. Of course beauty, ever-fleeting in this profession more than others, wasn’t meant to be.

It’s easy to forget about an athlete’s contributions to a franchise when his shortcomings stand out among those of his peers. It’s easy to forget about a veteran redefining his own game and the very portfolio of skills he entered the league with when one’s favorite basketball team isn’t winning.

It explains why, despite having finally established himself as a legitimate quality guard on two upstart young franchises in both Washington and later Cleveland, Hughes – a symbol of a failed revolution for which he was never even personally responsible – was demonized, ostracized and cast aside at the drop of a hat.

It’s 2007 and a kid from Ohio has a problem. His Cleveland Cavaliers, LeBron James’ Cleveland Cavaliers, aren’t winning as many ball games as they’re supposed to. Before long, HeyLarryHughesPleaseStopTakingSoManyBadShots.com is a registered domain. After before long but still before actual long, it becomes a full-fledged thing, a cultural meme, an internet sensation.

He’s not wrong, the two-guard ultimately shot .377 from the field that 2007-08 season before his eventual trade to the Chicago Bulls, but the message remains. There’s no time to support the stars of yesterday, when those of today have arrived to right the ship. Go away, Larry.

Perhaps it’s poignant that Hughes ended up in Cleveland alongside James when he did, his fade to obscurity overshadowed by the true heir of the NBA’s throne taking his position. Seemingly overnight James rose up, pardoning Vince Carter, Tracy McGrady and the rest of the underachieving band of their responsibilities as the faces of the game.

While Carter’s and McGrady’s ultimate declines may have taken different, longer paths than, say, Hughes’, Rider’s or Stackhouse’s, there’s no denying that they started and finished in more or less the same place.

With the trade to Chicago, the same one that sent Ben Wallace to Cleveland, Hughes’ tenure as a contributing factor on a relevant basketball team came to a close.

Chapter 4

Hughes’ story was only just beginning.

In this case, it begins with tragedy, the death of a young man, a 20-year-old hoops head and brother.

In the spring of 2006, the Cavaliers organization took a break from a heated playoff series with the Detroit Pistons to mourn the loss of Justin Hughes.

If Justin’s name sounds familiar, it’s because it’s as inextricably linked to this account of an athlete’s career as basketball is itself. See, we don’t think of this when we’re reading our blog posts or watching our broadcasts, we don’t think of it when we’re registering domain names, but it’s hard to play basketball when your heart beats for nothing.

After a trying nine years following a perilous full cardiac transplant, Justin – Larry’s younger and only brother – quietly passed. The transplant bought Justin nearly a decade longer on Earth, nearly a decade more time to grow and share with his pro baller brother and indomitable single mother, but it was far from enough.

Unsurprisingly Larry wasn’t the same afterward, not on the court and certainly not off of it. This is what life can do to us.

Chapter 3

There was something sexy about the Washington Wizards back in the early 2000s. The organization coming off of a wretched Y2K was just finally showing signs of life in the wide-open Eastern Conference. There was a pulse in the Nation’s Capital, and it came, fittingly enough, with Michael Jordan himself on the roster.

Hughes arrived in D.C. in the second year of Jordan’s ill-fated comeback, serving as the club’s tertiary option behind MJ and Jerry Stackhouse. The Wizards came together, a marriage of various generations bound by their superficially similar niches like an NBA version of The Expendables.

When Jordan rereretired, the franchise sputtered, ultimately losing ground before Hughes and former teammate Gilbert Arenas accepted the task of breathing new life into the organization.

It was here, during the 2004-05 campaign, that Hughes truly blossomed. While he’d shown similar promise previously as a member of the Golden State Warriors, it was here where it mattered most. The team was winning.

With Jordan gone and Stackhouse by then in Dallas, Hughes – alongside Arenas – finally unloaded the years of oppression he’d been bottling inside him. Suddenly the years of hype started to make sense. He might not have reach Jordan-level, or even that which McGrady and Carter flirted with in Orlando and Toronto, respectively, but it was a fascinating change of fate.

It started as early as the regular season started, twice in his first five appearances Hughes topped the 25-point mark, by the end of November he was hanging 20-9-12 near-triple doubles and an emphatic 33-10-10 line the very next game.

Hughes struck for 30 three times in four games between December 29th and January 4th, but most importantly, his Wizards were winning. A seven-game win streak from Jan. 2-15 in which Hughes averaged 25.6 points per game? No problem. The streak ended the next night with Hughes in street clothes.

When he later returned to the lineup it was much of the same, he’d even go on to drop 30 points twice in an Eastern Conference quarterfinal matchup against the Chicago Bulls that they would ultimately close out in six games.

With Hughes shooting an acceptable .430 from the field, playing some of the game’s best perimeter defense and absolutely dazzling alongside Arenas and Antawn Jamison, the Wizards put forth their highest win total (45) since 1978. To this day, it hasn’t been topped.

The waiting, both for opportunities on a depth chart and in hospital lobbies with his mother, Vanessa, all led to this.

Chapter 2

When the calendar flipped to the Year 2000, we all struggled to find our places. For most of us, it was as simple as trying to make sense of Linkin Park’s incomprehensible Hybrid Theory, still reeling from the toll that movies like Memento and Requiem for a Dream had taken on us. We chatted smugly with our friends over ICQ and MSN Messenger, the sounds of Bryan Cranston as Hal – not Walter – echoing from the not-so-flatscreen televisions in the other room.

For Hughes and the Post-MJ generation of up-and-coming NBA stars, it meant injecting new life into a billion-dollar industry while simultaneously trying to navigate the perilous waters of adolescence in a family stricken with anxiety and grief.

The turn-of-the-century Golden State Warriors were a sight to behold, for reasons other than their questionable jerseys. It was satisfying to see Hughes post his relatively empty 22.7 points per game following the mid-season deal that sent him from the Philadelphia 76ers to Oakland, his healthy 14-year-old brother and mother often seen cheering passionately from the crowd.

Prior to, things were different.

In Philly, Hughes was a fresh, young, combo guard charged with the task of inspiring a new generation of fans stuck on an organization that already had somebody cast to do exactly that.

For as much as Allen Iverson was a shooting guard trapped in a point guard’s body, Hughes was the opposite, he just hadn’t come to terms with it yet. Together, the two struggled and the Larry Brown-led Sixers soon found a more compatible backcourt mate in the less conspicuous Eric Snow.

Hughes, of course, was just 19 years old when he was drafted into the NBA, an NCAA star who left the comforts of hometown Saint Louis University in order to help his mother foot the medical bills for Justin, so one can’t blame him for failing to seamlessly molding into place behind the most unconventional superstar in league history.

Maybe not back then, but in the grand scheme of things, it didn’t matter.

Chapter 1

The nine years that Justin would go on to enjoy following his heart-replacement surgery in 1997, of course, didn’t come free. If only all families on the donor transplant list had six-and-a-half-foot-tall family members with otherworldly leaping abilities.

After making the wise-beyond-his-years decision to stay local following the conclusion of his superstar prep career, Hughes celebrated his selection as the Sporting News collegiate freshman of the year by entering the NBA Draft as an underclassmen.

When at times it seemed the best way to take care of his kid brother was by quitting basketball altogether, the fact that he persevered and was able to give his family an opportunity they may not have otherwise been privy to, speaks volumes for the man he’s been all along.

His frame may not have been NBA-ready, his on-court mentality perhaps far from it, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t still the best decision of his life to declare early and set out for life as a professional athlete.

While hindsight’s view of the journeyman’s NBA career may leave much to be desired in terms of on-court accomplishments, you’d be hard-pressed to find somebody who got more out of their talent.

Sometimes the most impressive things in life happen before we’re ready to appreciate them.

[php snippet=1]