The gory details of Tommy John surgery

Although they are prone to a variety of injuries, there is one particular injury that pitchers desperately try to avoid. It involves three words that strike fear in the heart of any hurler: Tommy John surgery. The infamous procedure is considered to be very serious as it involves a long period of recovery. However, it is also a remarkable operation that has prolonged many careers.

“Dr. Frank Jobe’s development of the Tommy John procedure had a significant impact on sports medicine,” says Dr. Michael Reinold, physical therapist, medical blogger and rehabilitation coordinator for the Boston Red Sox. “His creativity and intuition helped spur a group of other surgeons such as Dr. James Andrews, Dr. David Altchek, and many more, to focus their energies on treating athletes and advancing surgical skills to help individuals return to sport.”

The official medial term for Tommy John surgery is ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction or UCL reconstruction. The ulnar collateral ligament is located in the elbow. It connects the humerus (the bone that runs from the shoulder to the elbow) with the ulna (the bone that runs on the medial side of the forearm). Pitchers put intense pressure on the elbow when throwing. Too much pressure can cause this ligament to tear, affecting the pitcher’s velocity and accuracy.

The actual procedure is literally similar to putting new laces on a shoe. The damaged ligament is replaced by a tendon taken from another area in the body. Using a figure-eight pattern, the tendon is then inserted through holes drilled in the humerus and ulna.

[php snippet=1]

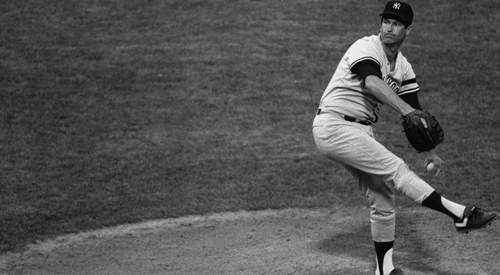

In 1974, Tommy John, a 31-year-old left-hander with the Los Angeles Dodgers, became the first professional athlete to successfully undergo the operation. At the time, a torn UCL usually meant the end of a pitcher’s career and many thought John would suffer the same unjust fate. However, he miraculously returned in 1976 and continued playing until 1989. John’s ground breaking surgery was performed by Dr. Jobe, a former team physician with the Dodgers.

It’s important to remember that a ligament connects bones, whereas a tendon attaches a muscle to a bone. Therefore, lengthy rehabilitation is required in order for the tendon to get used to its new role.

Following the operation, the pitcher must wear an elbow brace for a week. He then begins exercising in the second week to regain a range of motion. Every recovery program is different. But typically, the pitcher starts a throwing program four months after the procedure.

According to a 2003 USA Today article by Mike Dodd, the pitcher will start on flat ground and toss softly from 45 feet. There will be one set of 25 tosses, which is followed by a rest and then another set of 25. The practice is conducted every other day, with the distance slowly increasing after a few sessions. At the six-month mark, the pitcher will then start throwing off the mound, using just 50% of his ability. Gradually, he will increase the intensity and begin to include specialty pitches. By the eighth month, the pitcher will start throwing in “game conditions.” This involves throwing during batting practice, taking part in simulated action and pitching in low-level minor league matches. Although most pitchers can return to regular competition around the one-year mark, it sometimes takes an additional year for the pitcher to return to his proper form.

As noted by Dodd, most pitchers who undergo the procedure and have a successful recovery stress two important factors. First, it is vital to be patient. It takes a while for the converted ligament to gain enough strength to withstand normal throwing. Second, it is also vital to exercise the shoulder – in addition to the elbow – to ensure proper strength throughout the arm.

Dr. Reinold also points out that due to the success of the procedure, there is almost a false sense of confidence that all pitchers will return from UCL reconstruction.

“I have even heard some people state that they want to get the surgery so that they can return stronger than preoperatively,” exclaims Reinold. “It is almost as if there is a misconception that not only is it easy to return to pitching after surgery, but that it is likely that you will come back better than before.”

Reinold states that a return to sport requires a significant amount of work during rehabilitation.

“Although our success rates are close to 85-92% in elite pitchers, other studies have shown only 74% of high school pitchers return to play,” he says. “Bottom line, if you have this procedure, there is going to be a lot of hard work for an entire year or more.”

Aside from pitchers, fielders may require Tommy John surgery. Boston outfielder Rocco Baldelli is one such example. However, this type of occurrence is rare.

“You do see UCL reconstruction in other position players within baseball, but at a far less common frequency,” says Reinold. “Two factors come into the play: First, the force that is developed while pitching is much higher than throwing while fielding. Second, the quantity of pitches is significantly higher with pitchers. Because of this, an injury to a fielder’s UCL is less common and more likely to respond to non-operative treatment.”

Other athletes such as javelin throwers, tennis players, and football quarterbacks are also prone to UCL tears. But Reinold says the force and repetition that causes their injuries is less when compared to pitchers.

The notion of Tommy John surgery is a scary thought to any pitcher. This is due to the long journey one must take when they are required to have the operation. However, the end result tends to have many benefits. Of course, the procedure does not necessarily mean a pitcher will return and perform better than he did previously. But it is certainly more attractive than the alternative.

[php snippet=1]