From AD to RGIII: The ACL Tear Epidemic

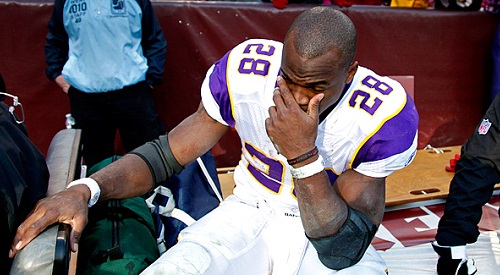

When the 2012 NFL season started on September 9, 2012, you could be excused if you hadn’t drafted Adrian Peterson for your fantasy football team. After undergoing an ACL reconstruction only eight months earlier, many doubted that Peterson would be ready for the start of the season, and if he was, they certainly weren’t expecting the type of season that followed.

Racking up 2,097 yards (only nine yards short of Eric Dickerson’s single-season rushing record) on his way to being named the NFL’s Most Valuable Player, Peterson silenced any doubters and recalibrated what we’ve come to expect as “typical” in the recovery from ACL reconstruction. While there is no doubt that improvements in surgical technique and rehab protocols have allowed for athletes to return more quickly, establishing Peterson’s trajectory as the new baseline may be underestimating the true magnificence of the season we’ve just witnessed, not to mention set up some unrealistic expectations for those who follow him.

It has long been thought that in the world of sports medicine “everyone’s recovery is different” and this is no different when it comes to an ACL injury. While it’s natural to want our favorite athlete back on the playing field as soon as possible, their return will often be based on a multitude of factors, some glaringly obvious (their age, injury history) and others more complex in nature (the surgeon’s technique, the athlete’s mechanics). While appropriate rehab will require an athlete who is motivated, driven and determined; all these buzzwords may not be enough to guarantee an outcome similar to Peterson’s.

[php snippet=1]

Consider the saga of Robert Griffin III. While he may flash a pair of Superman socks from time to time, his right knee has proven he isn’t the “Man of Steel”. After undergoing surgery for an ACL repair in 2009 while at Baylor, RGIII suffered a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) sprain in a regular season game this year against Baltimore. A few weeks later, Griffin controversially decided to play in a first-round playoff game against the Seattle Seahawks. During this game he re-injured the LCL and his surgically repaired ACL, requiring further surgery. While sharing the same surgeon as Peterson (Dr. James Andrews) makes it tempting to compare the two, Griffin’s past history could certainly delay his return. Players who tear their ACL a second time (or more) are more susceptible to re-tears, and after the Redskins took so much heat for “gambling” with their star player and his bum knee, don’t be surprised if the medical staff involved in his care take a more cautious approach when it comes to allowing him back on the field.

Griffin’s injury is also a reminder that ACL injuries rarely occur in isolation. While Peterson also tore his medial collateral ligament (MCL) this is often non-surgical in nature. Griffin on the other hand required a repair on his injured LCL while also undergoing his ACL reconstruction. This added procedure is more likely to skew the timeline for recovery in a lengthier direction. Associated injuries often get less publicity than the “media darling” that is the ACL, but they can be just as problematic when it comes to rehab and return to sport.

A total of 80-90% of ACL tears present with “bone bruising” which often results from the forceful impact between the femur and tibia during the tearing of the ACL. Bone bruises often present with severe pain lasting up to a few months after the trauma. Damage to the meniscus (or cartilage) of the knee are also found in 75% of ACL injuries. Not only will the loss of cartilage result in pain and a reduction of knee function, but it can also lead to earlier degeneration of the knee. In spite ofa movement for accelerated rehab following ACL surgeries, these types of associated injuries may slow down even the most dedicated athlete.

Four months following Peterson’s ACL tear, Derrick Rose, another athlete at the top of his game also suffered a torn ACL/MCL. While it would be tempting to compare the recoveries of two MVP-caliber athletes with similar injuries and no past history of ACL damage (and many have tried), their athletic prowess is where the comparison should begin and end. Peterson’s injury was the result of direct contact, which tends to be a fluke accident requiring a force to be applied on the wrong place at the wrong time. On the other hand, Rose’s injury occurred on a rather innocuous looking jump stop. It may not have looked like much, but this is a classic pattern for an ACL tear:

An athlete lands from a jump with significant force while the knee falls inward with rotation. A mechanism like this is often the result of modifiable factors like poor mechanics, poor muscle patterning/timing, poor coordination, fatigue or a combination of each. All of these factors must be identified and re-trained in order for a player like Rose to be ready for his return to the hardwood. Players who suffer an ACL tear with a jumping mechanism (like Rose) are also hampered by the fact that they are more likely to suffer cartilage tears than their non-jumping counterparts. Once again, these associated tears are likely to keep the athlete out of the game a little longer than an ACL tear in isolation.

For today’s athlete, a torn ACL is no longer the death knell for their career that it once was, but there is still a wide variability in the time for recovery and their level of ability upon returning to sports. While Adrian Peterson has provided a blueprint for an “ideal recovery”, it’s important to consider that “ideal” is still a long way from “typical.”

[php snippet=1]