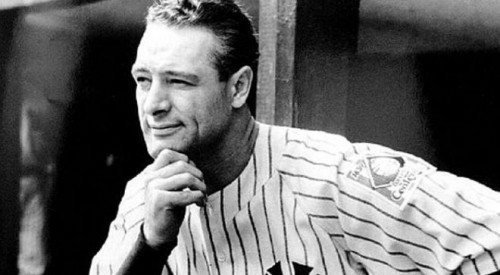

Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (2005)

Rating: 8/10

It still boggles the mind to think about Lou Gehrig and his consecutive game streak. Sure, it was broken by Cal Ripken Jr. a few years back, but the 90s were a different time: Ripken played in a time of physical conditioning, specialized team doctors and better medicine. Gehrig played back when the trainer’s job was to rub players down.

At the same time, there was much, much more to Gehrig than the streak. And in “Luckiest Man”, a detailed, meticulously researched and heartbreaking read, journalist Jonathan Eig shows Gehrig as a complex figure, both one of the brightest stars in baseball and a quiet, insecure man.

To most, Gehrig has come down to us for two things: a famous speech he made on July 4, 1939 (and what lends this book its title) and a mind-blogging streak of consecutive games played, never mind that it’s been broken. This book does a lot to show how important he was: a powerful hitter, a good fielder and someone who excelled in pressure situations.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t appreciated in his day; Gehrig certainly was. He was a two-time MVP, finishing as runner up two more times. It’s more because what he was so good at wasn’t in wide use: he was often compared to Babe Ruth, who could slug dozens of dingers. But Gehrig excelled in other ways: he hit for power but led the AL in On-Base Percentage five times. And in the postseason, he was one of the best hitters of all time.

[php snippet=1]

But there’s a lot more to Gehrig than just a star player. He comes alive in Eig’s book, a man uncomfortable in public, who stands to the side at parties and leaves without saying goodbye. He was insecure, willing to accept whatever offer the Yankees made, and a mama’s boy, living with his parents until he was 30. His complex personality makes for an interesting biography, full of moments where he leaps out as a hell of a player and others where you’re not sure what to make of the guy. One assumes many of his peers felt the same.

As the book goes deeper into Gehrig’s life, it becomes more and more tragic. Right as Gehrig started having his best seasons and not to mention finally becoming successful off of it, ALS quickly shredded apart his career and body. He wasn’t the first person to die from ALS but nobody was more publicly hit by it. His massive frame shrank as his muscles atrophied, his skills depleted as he struggled to hit and field balls and eventually, he removed himself from the lineup, breaking his consecutive game streak.

He was only 36, he was going downhill fast and mostly in the public eye. Before long, he wasn’t able to carry the lineup card to home plate, let alone take part in warm ups. During the World Series, one player remembers Gehrig “shuffling his feet like an old man in slippers,” just to get around.

He left baseball in 1939 and was elected to the Hall of Fame later that season. This period of Gehrig’s life is punctuated by correspondence between him and his doctors. Knowing what’s going to happen, reading him expressing hope he’ll recover is heartbreaking. Eig quotes liberally from Gehrig’s letters, letting him speak for himself. Often, Gehrig says there’s a 50/50 chance he’ll recover and is always optimistic of some new cure. Instead, Gehrig died about two years after his final at-bat.

“Luckiest Man” is a biography with some serious scholarship behind it. It must’ve been hard to get into Gehrig’s private side: he left behind no children or siblings, his wife died nearly 30 years ago and both parents are long dead. But Eig was able to track down some of Gehrig’s surviving letters and speak people who played either with or against him. We’re fortunate Eig was able to get these first-hand accounts; many of these people have since died. I think he went to lengths to paint an accurate picture: he includes some 30 pages of notes, comprising interviews, books and oral histories.

While “Luckiest Man” is a good and occasionally moving read, there’s a couple things irking me here. For one, Eig constantly relies on boxcar statistics like RBI, Home Runs or Battling average to show how good Gehrig was, often ignoring statistics like On Base or Sluggling Percentage that do a better job of proving his point. Given how he used Bill James (a big proponent of using these numbers) to project healthy Gehrig’s stats, it’s a curious omission. Another is Eig’s nasty habit of repeating himself: events are described two or three times, the same people introduced in two different chapters.

Still, this is probably the definitive book on Gehrig and a fun read to boot. It’s not quite at the same level as the benchmarks of sports biographies – David Maraniss’ “When Pride Still Mattered” or Richard Ben Cramer’s “Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life” – but not far behind them either. Recommended for sports fans, especially those into the golden years of baseball.

[php snippet=1]