Summer of ’49 (1989)

Rating: 8/10

It’s the cliche rivalry in baseball and arguably all of sports: the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees. Throughout the history of baseball, it’s been the one lasting true rivalry; it’s gone nearly 100 years. And if you’re not a fan of either team, it’s hard to really care about the rivalry.

On the surface, that’s the biggest problem with David Halbertam’s Summer of ’49. It’s heavily researched and full of little nuggets from that bygone season, but if you find the Yankees and Red Sox especially the Sox of the recent past odious, well, why would you want to read a book about them playing 60 years ago?

What saves Summer of ’49 from being just a book for those few, is how it’s more than just an account of that summer. It’s an examination of baseball at that period, when it was on the cusp of change. Halberstam moves to and from an account of the season with smaller portraits of the major players, illuminating what life was like back then for the team, for it’s owners and for those who followed the team, either as fans or in the media.

It’s been 60 years since the events of David Halberstam’s Summer of 49 happened and 20 years since it was first written but it’s remarkable how the book can be both quaint and timeless.

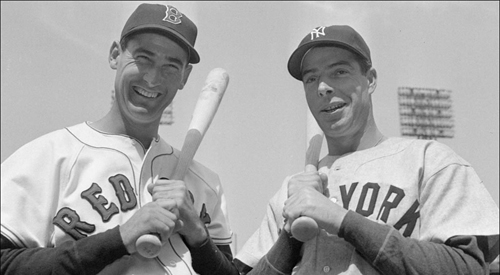

That summer, the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees battled for the American League title, with Boston making a massive late-summer surge that brought the pennant race down to the last few games of the season.

[php snippet=1]

In a lot of ways, the game Halberstam describes is alien by today’s standards. Players still travelled by train, were still bound to a team by the reserve clause and still had to work during the offseason to make ends meet. Owners still dictated salaries, often directly to players. In his second season, Joe DiMaggio hit .346 with 46 home runs, and was paid $15,000. He asked for a raise to $40,000 for his next season, but ended up with $25,000.

While some players loomed large enough to eke out a living by playing ball Ted Williams, Yogi Berra, etc. others had to balance it by working in the offseason; thus winning, with a bonus World Series check, likely meant much more to the players.

Of course, there was one player for whom winning meant a lot, money or not: DiMaggio. His shadow looms more than any other player in this book (although he was one of the few not interviewed by the author), even though he missed stretches of the season with injury. Halberstam writes of the tremendous pressure that DiMaggio had to live through: aging fast, battling injuries all season and no longer at the top of his game, but still forced to lead the Yankees in the media capital of the world.

It was a different time to be a player: with so many papers and no radio or TV from which to speak for themselves, players were either lauded (as New York writers did to DiMaggio) or crucified (as Boston writers did to Ted Williams) by the media, with little ground in between. The bitterest battle was between Williams and Dave Egan, a columnist for the Boston American. It’s jarring to read some of the full-bore attacks on Williams and how they were met without any criticism.

The difference between how Williams was treated in Boston and DiMaggio in New York is amazing. Where writers treated Williams with scorn, DiMaggio was lauded.

Of course, it was the back room dealings that led to this. By and large, sportswriters have always been somewhat insecure; when DiMaggio was willing to embrace and have drinks with them at Toots Shor’s, they repaid him in compliments. And when Williams was tirelessly devoted to his craft and not into playing games with them, they tore him a new one.

It was a different time for the sport of baseball too, writes Halberstam. College football was still big, but only mattered to the select few who actually went to university and both pro basketball and football were still years away from mainstream acceptance (the NHL goes unaccounted for by Halberstam). For many people, mostly first and second generation Americans, baseball was the sport.

Especially interesting is Halberstam’s account of how baseball was broadcasted in those days. Radio was still the main way most people experienced baseball, with announcers like Mel Allen or Red Barber not so much recounting the game as recreating it for fans.

There’s a good anecdote about Ronald Reagan and his days of being an announcer: he was calling a Cubs game by proxy, sitting in a studio booth and reading a play-by-play as it came off the wire. One time the wire went dead and Reagan was forced to improvise, calling a series of foul balls and delays. When he got the connection back, he found his batter had struck out ages before and he had to work his way back to reality. The disconnect between him the announcer and the fan, sitting at home by a radio, left baseball in position to be rhapsodized.

Today, people will watch a Dodgers game to listen to Vin Scully. In the past, people listened to Yankee broadcasts to hear Red Barber.

But television, recently introduced into the sport and still in it’s earliest stages, was already waging a revolution for the way people could see the sport. No longer was one reliant on an announcer to set the game up for them: they could see it for themselves. And as games moved from the day to evening, people quickly learned how to capitalize on this new technology; for example, bars would advertise what games they were showing that week on their TV.

At the same time, owners worried about how broadcasts would affect attendance so much so, that one owner limited what angles could be used for the broadcast; having a camera at first and third base was okay, but having one in the bleachers facing home plate was not.

With these asides, Halberstam not only retells the season, but he recreates the period, when baseball wasn’t America’s pastime but America itself: something about to change and explode into something much larger and encompassing, yet largely afraid and unwilling to change.

But, in spite of all the book’s retroactive reporting, one cannot escape a feeling of sentimentality. The players interviewed, and the ones Halberstam describes but doesn’t talk to (DiMaggio, especially), are all people he looked to. He’s a journalist, sure a Pulitzer Prize winning one, no less but he’s also a fan. As he writes in his afterward, he was 15 in 1949, and he was a fan of the Yankees. This season, the one he chronicles, means something to him.

This is a passion that clearly carries over into the writing. Summer of ’49 is an enjoyable read and one baseball fans even those who despise both Boston and New York will like.

[php snippet=1]