The fall and rise of UFC

The very first match of Ultimate Fighting Championship’s history exemplified what the company would be known for immediately thereafter: unadulterated, no-holds-barred violence. It was “human cockfighting,” as Senator John McCain put it.

Back in 1993, the 216-lbs. Gerard Gordeau took on 410-lbs. sumo wrestler Teila Tuli. It was the first knock out in UFC history, taking approximately 20 seconds to draw blood and only three more to end the fight. Instantly the company drew the label as a “blood sport.”

While there were rules against eye gouging and biting, things like head butting, hair pulling and groin shots were merely frowned upon.

Groin shots. Frowned upon.

There certainly wasn’t any smiling when, at UFC 4, Keith Hackney took full advantage of this by unleashing a string of crotch shots on Joe Son.

The fledgling UFC was vicious and inhumane, but, most of all, captivating.

Still, they had trouble staying on Pay-Per-View due to the violence. The fights were brutal. They could only end with a knockout, submission or stoppage due to cuts. And because of the tournament format used in the first eight UFC events, fighters were always hurting.

After defeating a man twice his size, Gordeau then had to face Kevin Rosier that same night in the semifinal. Next was legend Royce Gracie in the final. Three fights in one night for both Gordeau and Gracie. These days, fighters rarely have more than three fights in an entire year.

Obviously, things had to change.

[php snippet=1]

The first thing to go was the manner in which fights ended. A 20-minute match time limit was instituted for the tournament matches for UFC 5. Another first was the single-match “Superfight” between Royce Gracie and Ken Shamrock, which was irrelevant of UFC 5’s tournament and more similar to the single-bout cards the UFC features today.

Over the next three years, many rules were introduced by state athletic commissions to clean up the sport. Weight classes were adopted for UFC 12, gloves were a necessity for UFC 14, and UFC 15 finally barred tactics like head butts, hair pulling and, probably much to Joe Sun’s joy, groin strikes. Improving on the time limit, UFC 21 used two five-minute rounds, three five-minute rounds for main events, and five five-minute rounds for championship fights. Judges also started using the 10-point must system seen in boxing.

The UFC now had a marketable product.

Regardless, it had yet to develop a serious fanbase due to being considered somewhat of a novelty act. UFC was not allowed in 36 states due to bills passed just prior to McCain’s “human cockfighting” comment. New York decided to enact the ban just prior to UFC 12, leading them to relocate the event to Alabama. They were struggling to get events on Pay-Per-View too.

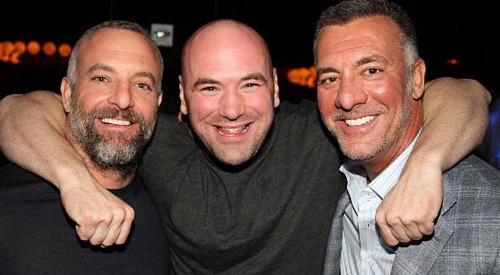

Enter Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta with their friend, Dana White.

In January 2001, the trio bought the near-bankrupt UFC from Semaphore Entertainment Group owner Robert Meyrowitz for a mere $2 million.

The Fertitta brothers acquired their fortune via the Station Casinos in Las Vegas. A parent company to the UFC, Zuffa LLC, was created by the three that same month.

With the help of Lorenzo Fertitta’s past membership in the Nevada Athletic Commission, they quickly secured sanction in state, allowing them to be taken more seriously and helping them get back onto Pay-Per-View.

Next was making the company visible. Advertising greatly increased. More posters were made and ads started popping up. More sponsors joined the venture, and new VHS and DVD releases added more sources of revenue. Things weren’t great but UFC had income.

Yet they needed something to capture the attention of people, especially those who weren’t familiar with the sport. And nothing gets people more excited to see blood than a good old fashion feud.

It started in 1999 at UFC 18 when Tito Ortiz was just beginning his career. At the time, Ken Shamrock was a coach for the Lion’s Den team who was being represented by Jerry Bohlander in his fight against Ortiz. After defeating Bohlander, Ortiz put on a shirt that simply said “I just f**ked your ass.” Shamrock took notice.

At the next event, UFC 19, Ortiz defeated another Lion’s Den member, this time Guy Mezger, and pulled out another t-shirt that said “Gay Mezger is my Bitch”. Shamrock exploded, yelling at Ortiz from the top of the cage. The two jawed at each other before referee Big John McCarthy physically picked up Ortiz and carried him away.

Shamrock returned from his stint with the WWF to face Ortiz for the UFC Light Heavyweight Championship at UFC 40. The feud quadrupled the amount of buys compared to the average rate for past Zuffa-owned events. The MGM Grand had a near-capacity crowd with 13,022 tickets sold. They stood to make at least $1.5 million, then a record for the UFC, marking a first turning point for the company.

But the biggest payoff was the publicity. Both fighters appeared on The Best Damn Sports Show Period to trash talk. National media outlets like ESPN and USA Today covered the fight. They drew attention like no MMA fight in the United States has ever received.

UFC was benefiting from having recognizable fighters too. Around this time is when Hall of Famers like Ortiz, Shamrock, Chuck Liddell, Randy Courture, Matt Hughes, as well as future Hall of Famers B.J. Penn and Vitor Belfort all made an impact on the sport. With stars to market, feuds that need to be solved, and plenty of room to develop the brand, UFC was off.

UFC 47 in 2004, featuring Ortiz vs. Liddell, was the start of a consistent 100,000+ buys on Pay-Per-View. Still, more money was being put into the advertising and events than the shows were actually pulling in.

Seeing how well the Fertitta brother’s 2004 reality show American Casino promoted their casinos, it was decided the UFC needed something similar as a last ditch effort to thrust them into the mainstream to gain revenue. The result was The Ultimate Fighter.

In a tournament format, eight fighters from the light heavyweight and middleweight classes fought it out in separate brackets for six-figure contracts in the UFC. The show did exactly what it was supposed to do and more. It gave access to the fighter’s personal lives, which created favorites among the fans, heightening the stakes for the fights for survival. Not only that, but showing new, free fights on TV was rarely done and now audiences were treated to two every week.

Also, it shined light on how seriously the fighters took the sport and how much they had to sacrifice. This is highlighted by one of the greatest sports speeches ever, featuring Dana White cussing out the fighters at the start of the season who were under the impression they’d only be training, and not fighting, on the show.

Since then, White went from a behind-the-scenes promoter to the UFC’s spokesperson. His brash, honest personality helped push the company over the hump by giving the public a likable, business savvy figure who popped into anyone’s mind when they thought “UFC.”

Then there was the finale between Forrest Griffin and Stephan Bonnar, one of the greatest fights in MMA history. The two warriors went at, it wanting nothing more than that UFC contract. By the final bell, both were beaten and bloodied to the point of being unrecognizable. That single fight, unsuspectingly, can be considered the second turning point in UFC’s history, helping usher it into the mainstream. The entire first season of The Ultimate Fighter changed the course of the UFC for the better.

UFC knew it was on the rise. The best way they could tell was by witnessing all of the competing MMA companies popping up. UFC used its big dog status to purchase and absorb the other companies, like World Extreme Cagefighting (WEC) and local rival World Fighting Alliance (WFA) in 2006, Pride Fighting in 2007, and Strikeforce in 2011.

It’s still too early to tell, but the 2011 partnership with Fox could mark the third turning point. Getting a seven-year contract will bring MMA even closer to the public. It satisfies both the fans and the UFC by giving viewers free fights they would usually have to pay for while the UFC greatly broadens their audience by reaching out to those who normally wouldn’t give the UFC a thought, or those who aren’t able to afford the events. It really shows how far they’ve come too. As Dana White told ESPN regarding the Fox deal, “the UFC was not allowed on Pay-Per-View and our goal was to get on network television so I’d have to say that’s our biggest achievement.”

With all the money rolling in, the UFC is now estimated to be worth approximately $2 billion. That’s a net worth increase of 1,000 percent from when the Fertitta brothers and White bought it for $2 million in 2001.

They still aren’t done.

“Everything is going to change in the next two years,” White told MMAJunkie.com. “That’s what we’ve been doing though. We’ve been trailblazing… We’re going to shock the world again in the next two years.”

Things like creating a women’s division and targeting the next generation who are growing up with MMA are in the plans. But mostly, UFC is looking to go global.

“Every country. We want this sport to be the same as soccer,” White said. ”Meaning that the same game of soccer that we play here in the united states is the same game that people play all over the world.”

They already broadcast in 175 countries in 22 languages inside over a billion homes worldwide.

So while the story for the UFC is already a long one, it is far from complete. The future of sports may fall into the hands of MMA. After all, the NFL captivated audiences then grew at a rate similar to what the UFC is doing now. They’ve made incredible progress since the groin targeting cockfights of UFC 1 nearly 19 years ago.

[php snippet=1]