The Sweet Science (2004)

Rating: 9/10

On April 5, 2011, a Toronto Maple Leafs loss officially ended their playoff run. Almost like clockwork, the Toronto Sun began a series on what’s wrong with the Leafs in the next day’s paper.

The regularity of this kind of sportswriting, where a columnist takes it upon themselves to explain why a team’s model is broken and how it ought to to fixed, usually in something like 30 column inches, is far from new. Hell, there’s been books written on the topic.

While the regularity of these columns diminishes their impact, so does their scope. There are many things which went wrong with the Leafs in hindsight yet far fewer that can be seen up ahead. More often than not, these columns resemble postmortems from a television drama: “the victim died from a gunshot to the head,” says a coroner looking at a man with a hole in his head.

That’s why whenever I read them, or anything else where a writer takes it upon themselves to explain how they’d fix something overnight, I’m reminded of a line from A.J. Liebling:

“Part of the pleasure of going to a fight is reading the newspapers the next morning to see what the sports writers think happened. This pleasure is prolonged, in the case of a big bout, by fight films. You can go to them to see what did happen.”

[php snippet=1]

Liebling was an old-school newspaperman with a history at both The New York Times and The World and in 1935, he joined the fledgling New Yorker magazine. There, he wrote about anything and everything with consummate skill: from riding with the US Army as it roared through North Africa and France in the second world war to virtually inventing modern press criticism with his Wayward Press column to French cuisine.

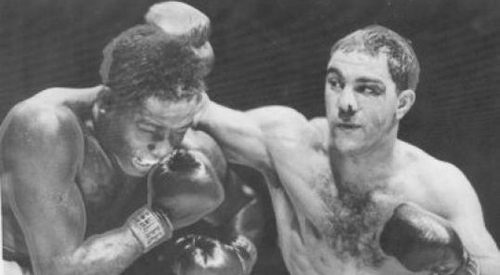

But some of his best writing was reserved for his passion: boxing. The Sweet Science is the best collection of Liebling’s writings on the subject. It’s a volume of essays written for The New Yorker between 1951 and 1956 which even now still pack a punch.

He wrote about fights as good as anybody and perhaps better than anyone. His pieces avoid the trappings and cliches of boxing stories by sidestepping themes of morality or danger. In his world, a fighter is somebody who’s job description includes punching people in the nose or has to be dissuaded from pigging out on hot dogs. There’s never a sense of danger from his pieces; Liebling wrote like the fan he was.

The biggest thing one takes away from The Sweet Science is how it’s never lacking in detail, from Liebling’s attempts to reproduce accents on the printed page to observations from around the event: the blue haze of a cigarette-smoke filled room, the name written on the back of a borrowed chair, a crowded bar after a controversial finish. Take this example, where Liebling describes what happened alongside his seat at a Rocky Marciano/Joe Louis bout:

“The punch knocked Marciano through the ropes and he lay on the ring apron, only one leg inside.

The tall blonde was bawling and pretty soon she began to sob. The fellow who had brought her was horrified. “Rocky didn’t do anything wrong,” he said. “He didn’t foul him. What are you booing?”

The blonde said, “You’re so cold. I hate you, too.”

His pieces take you all over. From a fight in a crowded garage, converted to an ad-hoc arena, in Donneybrook, Ireland to a crowded Yankee Stadium, hosting a fight at 11 p.m., and most memorably to the long-gone clubs and restaurants, gathering places for training fighters and fans of the fight game. Here he’s captured a moment in time, of boxers rebelling against trainers by eating hot dogs and riding in canoes, of an Irish crowd lurching between a riot to waiting for the next fight to begin, of suits and binoculars, cigarettes and the Polo Grounds.

Not to mention how well researched this book is: Liebling was a longtime fan of boxing who rubbed elbows with trainers and fighters and his pieces turned middleweights into fighters from the Song of Roland and elevated the all-but-forgotten Pierce Egan to “the Herodotus of boxing” through his liberal quoting. It’s hard to imagine too many current writers dropping names like that without sounding pretentious.

It extends beyond reading, though; Liebling had a knack for reading the tea leaves. For example, Liebling not only foresaw the negative impact television would have on boxing, he explained how it could be fixed:

“In the long view, the best hope for the revival of the dulcet art is that as the television boxing shows run out of new talent, the big and silly television audience will lose interest in them, and national sponsors will let them drop. Then the small clubs will start up again, for the hard core of customers who like boxing well enough to pay for it, but now get it for free.”

Unlike today’s writers who look backwards to explain what’s gone wrong, Liebling was able to look ahead and see what would go wrong, namely that the promise of exposure would lure fighters away from small fights and hurt the lower levels – the foundation – of the sport.

And it’s that mix between smarts and fun which keeps me coming back to Liebling. It’s one of those rare books which I find myself going back to again and again because it’s such a joy to read: the way in which he wrote about the fights was not only all but unprecedented, but is still fresh today. It’s no small surprise that writers continually sing his praises, from The New Yorker editor David Remnick to novelists like the late Mordecai Richler.

However, one dissenting voice is Joyce Carol Oates, who, in her On Boxing, notes that Liebling has a “jokey, condescending, occasionally racist attitude towards his subject.” There are times when I’m inclined to see her point, such as when Liebling calls “Hurricane” Jackson – a boxer who could neither read nor write – an animal. One is left with a confused impression from this: while Liebling is cruel to him in print, he’s more than gracious to other boxers.

Ultimately, it’s a minor curiosity in a seminal work. Sports Illustrated once called The Sweet Science the best sports book ever written. It’s hard to disagree. It represents the best kind of sportswriting: vivid, timeless and utterly free of cliche.

[php snippet=1]